DATENSCHUTZERKLÄRUNG

Datenschutzerklärung

Name und Kontakt des Verantwortlichen gemäß Artikel 4 Abs. 7 DSGVO

EIGEN + ART Lab

Torstraße 220

10115 Berlin

Galerie EIGEN + ART GmbH & Co. KG.

Berlin:

Auguststraße 26

D-10117 Berlin

Telefon +49 30. 280 66 05

Fax +49 30. 280 66 16

berlin@eigen-art.com

Leipzig:

Spinnereistraße 7. Halle 5

D-04179 Leipzig

Telefon +49 341. 960 78 86

Fax +49 341. 225 42 14

leipzig@eigen-art.com

Datenschutzbeauftragter

Name: Gerd Harry Lybke

Anschrift: Auguststraße 26, D-10117 Berlin

E-Mail: berlin@eigen-art.com

Sicherheit und Schutz Ihrer personenbezogenen Daten

Wir betrachten es als unsere vorrangige Aufgabe, die Vertraulichkeit der von Ihnen bereitgestellten personenbezogenen Daten zu wahren und diese vor unbefugten Zugriffen zu schützen. Deshalb wenden wir äußerste Sorgfalt und modernste Sicherheitsstandards an, um einen maximalen Schutz Ihrer personenbezogenen Daten zu gewährleisten.

Als privatrechtliches Unternehmen unterliegen wir den Bestimmungen der europäischen Datenschutzgrundverordnung (DSGVO) und den Regelungen des Bundesdatenschutzgesetzes (BDSG). Wir haben technische und organisatorische Maßnahmen getroffen, die sicherstellen, dass die Vorschriften über den Datenschutz sowohl von uns, als auch von unseren externen Dienstleistern beachtet werden.

Begriffsbestimmungen

Der Gesetzgeber fordert, dass personenbezogene Daten auf rechtmäßige Weise, nach Treu und Glauben und in einer für die betroffene Person nachvollziehbaren Weise verarbeitet werden („Rechtmäßigkeit, Verarbeitung nach Treu und Glauben, Transparenz“). Um dies zu gewährleisten, informieren wir Sie über die einzelnen gesetzlichen Begriffsbestimmungen, die auch in dieser Datenschutzerklärung verwendet werden:

Personenbezogene Daten

„Personenbezogene Daten“ sind alle Informationen, die sich auf eine identifizierte oder identifizierbare natürliche Person (im Folgenden „betroffene Person“) beziehen; als identifizierbar wird eine natürliche Person angesehen, die direkt oder indirekt, insbesondere mittels Zuordnung zu einer Kennung wie einem Namen, zu einer Kennnummer, zu Standortdaten, zu einer Online-Kennung oder zu einem oder mehreren besonderen Merkmalen identifiziert werden kann, die Ausdruck der physischen, physiologischen, genetischen, psychischen, wirtschaftlichen, kulturellen oder sozialen Identität dieser natürlichen Person sind.

Verarbeitung

„Verarbeitung“ ist jeder, mit oder ohne Hilfe automatisierter Verfahren, ausgeführter Vorgang oder jede solche Vorgangsreihe im Zusammenhang mit personenbezogenen Daten wie das Erheben, das Erfassen, die Organisation, das Ordnen, die Speicherung, die Anpassung oder Veränderung, das Auslesen, das Abfragen, die Verwendung, die Offenlegung durch Übermittlung, Verbreitung oder eine andere Form der Bereitstellung, den Abgleich oder die Verknüpfung, die Einschränkung, das Löschen oder die Vernichtung.

Einschränkung der Verarbeitung

„Einschränkung der Verarbeitung“ ist die Markierung gespeicherter personenbezogener Daten mit dem Ziel, ihre künftige Verarbeitung einzuschränken.

Profiling

„Profiling“ ist jede Art der automatisierten Verarbeitung personenbezogener Daten, die darin besteht, dass diese personenbezogenen Daten verwendet werden, um bestimmte persönliche Aspekte, die sich auf eine natürliche Person beziehen, zu bewerten, insbesondere um Aspekte bezüglich Arbeitsleistung, wirtschaftliche Lage, Gesundheit, persönliche Vorlieben, Interessen, Zuverlässigkeit, Verhalten, Aufenthaltsort oder Ortswechsel dieser natürlichen Person zu analysieren oder vorherzusagen.

Pseudonymisierung

„Pseudonymisierung“ ist die Verarbeitung personenbezogener Daten in einer Weise, dass die personenbezogenen Daten ohne Hinzuziehung zusätzlicher Informationen nicht mehr einer spezifischen betroffenen Person zugeordnet werden können, sofern diese zusätzlichen Informationen gesondert aufbewahrt werden und technischen und organisatorischen Maßnahmen unterliegen, die gewährleisten, dass die personenbezogenen Daten nicht einer identifizierten oder identifizierbaren natürlichen Person zugewiesen werden können.

Dateisystem

„Dateisystem“ ist jede strukturierte Sammlung personenbezogener Daten, die nach bestimmten Kriterien zugänglich sind, unabhängig davon, ob diese Sammlung zentral, dezentral oder nach funktionalen oder geografischen Gesichtspunkten geordnet geführt wird.

Verantwortlicher

„Verantwortlicher“ ist eine natürliche oder juristische Person, Behörde, Einrichtung oder andere Stelle, die allein oder gemeinsam mit anderen über die Zwecke und Mittel der Verarbeitung von personenbezogenen Daten entscheidet; sind die Zwecke und Mittel dieser Verarbeitung durch das Unionsrecht oder das Recht der Mitgliedstaaten vorgegeben, so können der Verantwortliche beziehungsweise die bestimmten Kriterien seiner Benennung nach dem Unionsrecht oder dem Recht der Mitgliedstaaten vorgesehen werden.

Auftragsverarbeiter

„Auftragsverarbeiter“ ist eine natürliche oder juristische Person, Behörde, Einrichtung oder andere Stelle, die personenbezogene Daten im Auftrag des Verantwortlichen verarbeitet.

Empfänger

„Empfänger“ ist eine natürliche oder juristische Person, Behörde, Einrichtung oder andere Stelle, denen personenbezogene Daten offengelegt werden, unabhängig davon, ob es sich bei ihr um einen Dritten handelt oder nicht. Behörden, die im Rahmen eines bestimmten Untersuchungsauftrags nach dem Unionsrecht oder dem Recht der Mitgliedstaaten möglicherweise personenbezogene Daten erhalten, gelten jedoch nicht als Empfänger; die Verarbeitung dieser Daten durch die genannten Behörden erfolgt im Einklang mit den geltenden Datenschutzvorschriften gemäß den Zwecken der Verarbeitung.

Dritter

„Dritter“ ist eine natürliche oder juristische Person, Behörde, Einrichtung oder andere Stelle, außer der betroffenen Person, dem Verantwortlichen, dem Auftragsverarbeiter und den Personen, die unter der unmittelbaren Verantwortung des Verantwortlichen oder des Auftragsverarbeiters befugt sind, die personenbezogenen Daten zu verarbeiten.

Einwilligung

Eine „Einwilligung“ der betroffenen Person ist jede freiwillig für den bestimmten Fall, in informierter Weise und unmissverständlich abgegebene Willensbekundung in Form einer Erklärung oder einer sonstigen eindeutigen bestätigenden Handlung, mit der die betroffene Person zu verstehen gibt, dass sie mit der Verarbeitung der sie betreffenden personenbezogenen Daten einverstanden ist.

Rechtmäßigkeit der Verarbeitung

Die Verarbeitung personenbezogener Daten ist nur rechtmäßig, wenn für die Verarbeitung eine Rechtsgrundlage besteht. Rechtsgrundlage für die Verarbeitung können gemäß Artikel 6 Abs. 1

lit. a – f DSGVO insbesondere sein:

Die betroffene Person hat ihre Einwilligung zu der Verarbeitung der sie betreffenden personenbezogenen Daten für einen oder mehrere bestimmte Zwecke gegeben;

die Verarbeitung ist für die Erfüllung eines Vertrags, dessen Vertragspartei die betroffene Person ist, oder zur Durchführung vorvertraglicher Maßnahmen erforderlich, die auf Anfrage der betroffenen Person erfolgen;

die Verarbeitung ist zur Erfüllung einer rechtlichen Verpflichtung erforderlich, der der Verantwortliche unterliegt;

die Verarbeitung ist erforderlich, um lebenswichtige Interessen der betroffenen Person oder einer anderen natürlichen Person zu schützen;

die Verarbeitung ist für die Wahrnehmung einer Aufgabe erforderlich, die im öffentlichen Interesse liegt oder in Ausübung öffentlicher Gewalt erfolgt, die dem Verantwortlichen übertragen wurde;

die Verarbeitung ist zur Wahrung der berechtigten Interessen des Verantwortlichen oder eines Dritten erforderlich, sofern nicht die Interessen oder Grundrechte und Grundfreiheiten der betroffenen Person, die den Schutz personenbezogener Daten erfordern, überwiegen, insbesondere dann, wenn es sich bei der betroffenen Person um ein Kind handelt.

Information über die Erhebung personenbezogener Daten

(1) Im Folgenden informieren wir über die Erhebung personenbezogener Daten bei Nutzung unserer Website. Personenbezogene Daten sind z. B. Name, Adresse, E-Mail-Adressen, Nutzerverhalten.

(2) Bei einer Kontaktaufnahme mit uns per E-Mail werden die von Ihnen mitgeteilten Daten (Ihre E-Mail-Adresse, ggf. Ihr Name und Ihre Telefonnummer) von uns gespeichert, um Ihre Fragen zu beantworten. Die in diesem Zusammenhang anfallenden Daten löschen wir, nachdem die Speicherung nicht mehr erforderlich ist, oder die Verarbeitung wird eingeschränkt, falls gesetzliche Aufbewahrungspflichten bestehen.

Erhebung personenbezogener Daten bei Besuch unserer Website

Bei der bloß informatorischen Nutzung der Website, also wenn Sie sich nicht registrieren oder uns anderweitig Informationen übermitteln, erheben wir nur die personenbezogenen Daten, die Ihr Browser an unseren Server übermittelt. Wenn Sie unsere Website betrachten möchten, erheben wir die folgenden Daten, die für uns technisch erforderlich sind, um Ihnen unsere Website anzuzeigen und die Stabilität und Sicherheit zu gewährleisten (Rechtsgrundlage ist Art. 6 Abs. 1 S. 1 lit. f DSGVO):

IP-Adresse

Datum und Uhrzeit der Anfrage

Zeitzonendifferenz zur Greenwich Mean Time (GMT)

Inhalt der Anforderung (konkrete Seite)

Zugriffsstatus/HTTP-Statuscode

jeweils übertragene Datenmenge

Website, von der die Anforderung kommt

Browser

Betriebssystem und dessen Oberfläche

Sprache und Version der Browsersoftware.

Kinder

Unser Angebot richtet sich grundsätzlich an Erwachsene. Personen unter 18 Jahren sollten ohne Zustimmung der Eltern oder Erziehungsberechtigten keine personenbezogenen Daten an uns übermitteln.

Rechte der betroffenen Person

(1) Widerruf der Einwilligung

Sofern die Verarbeitung der personenbezogenen Daten auf einer erteilten Einwilligung beruht, haben Sie jederzeit das Recht, die Einwilligung zu widerrufen. Durch den Widerruf der Einwilligung wird die Rechtmäßigkeit der aufgrund der Einwilligung bis zum Widerruf erfolgten Verarbeitung nicht berührt.

Für die Ausübung des Widerrufsrechts können Sie sich jederzeit an uns wenden.

(2) Recht auf Bestätigung

Sie haben das Recht, von dem Verantwortlichen eine Bestätigung darüber zu verlangen, ob wir sie betreffende personenbezogene Daten verarbeiten. Die Bestätigung können Sie jederzeit unter den oben genannten Kontaktdaten verlangen.

(3) Auskunftsrecht

Sofern personenbezogene Daten verarbeitet werden, können Sie jederzeit Auskunft über diese personenbezogenen Daten und über folgenden Informationen verlangen:

die Verarbeitungszwecke;

den Kategorien personenbezogener Daten, die verarbeitet werden;

die Empfänger oder Kategorien von Empfängern, gegenüber denen die personenbezogenen Daten offengelegt worden sind oder noch offengelegt werden, insbesondere bei Empfängern in Drittländern oder bei internationalen Organisationen;

falls möglich, die geplante Dauer, für die die personenbezogenen Daten gespeichert werden, oder, falls dies nicht möglich ist, die Kriterien für die Festlegung dieser Dauer;

das Bestehen eines Rechts auf Berichtigung oder Löschung der Sie betreffenden personenbezogenen Daten oder auf Einschränkung der Verarbeitung durch den Verantwortlichen oder eines Widerspruchsrechts gegen diese Verarbeitung;

das Bestehen eines Beschwerderechts bei einer Aufsichtsbehörde;

wenn die personenbezogenen Daten nicht bei der betroffenen Person erhoben werden, alle verfügbaren Informationen über die Herkunft der Daten;

das Bestehen einer automatisierten Entscheidungsfindung einschließlich Profiling gemäß Artikel 22 Absätze 1 und 4 DSGVO und – zumindest in diesen Fällen – aussagekräftige Informationen über die involvierte Logik sowie die Tragweite und die angestrebten Auswirkungen einer derartigen Verarbeitung für die betroffene Person.

Werden personenbezogene Daten an ein Drittland oder an eine internationale Organisation übermittelt, so haben Sie das Recht, über die geeigneten Garantien gemäß Artikel 46 DSGVO im Zusammenhang mit der Übermittlung unterrichtet zu werden. Wir stellen eine Kopie der personenbezogenen Daten, die Gegenstand der Verarbeitung sind, zur Verfügung. Für alle weiteren Kopien, die Sie Person beantragen, können wir ein angemessenes Entgelt auf der Grundlage der Verwaltungskosten verlangen. Stellen Sie den Antrag elektronisch, so sind die Informationen in einem gängigen elektronischen Format zur Verfügung zu stellen, sofern er nichts anderes angibt. Das Recht auf Erhalt einer Kopie gemäß Absatz 3 darf die Rechte und Freiheiten anderer Personen nicht beeinträchtigen.

(4) Recht auf Berichtigung

Sie haben das Recht, von uns unverzüglich die Berichtigung Sie betreffender unrichtiger personenbezogener Daten zu verlangen. Unter Berücksichtigung der Zwecke der Verarbeitung haben Sie das Recht, die Vervollständigung unvollständiger personenbezogener Daten – auch mittels einer ergänzenden Erklärung – zu verlangen.

(5) Recht auf Löschung („Recht auf vergessen werden“)

Sie haben das Recht, von dem Verantwortlichen zu verlangen, dass Sie betreffende personenbezogene Daten unverzüglich gelöscht werden, und wir sind verpflichtet, personenbezogene Daten unverzüglich zu löschen, sofern einer der folgenden Gründe zutrifft:

Die personenbezogenen Daten sind für die Zwecke, für die sie erhoben oder auf sonstige Weise verarbeitet wurden, nicht mehr notwendig.

Die betroffene Person widerruft ihre Einwilligung, auf die sich die Verarbeitung gemäß Artikel 6 Absatz 1 Buchstabe a oder Artikel 9 Absatz 2 Buchstabe a DSGVO stützte, und es fehlt an einer anderweitigen Rechtsgrundlage für die Verarbeitung.

Die betroffene Person legt gemäß Artikel 21 Absatz 1 DSGVO Widerspruch gegen die Verarbeitung ein und es liegen keine vorrangigen berechtigten Gründe für die Verarbeitung vor, oder die betroffene Person legt gemäß Artikel 21 Absatz 2 DSGVO Widerspruch gegen die Verarbeitung ein.

Die personenbezogenen Daten wurden unrechtmäßig verarbeitet.

Die Löschung der personenbezogenen Daten ist zur Erfüllung einer rechtlichen Verpflichtung nach dem Unionsrecht oder dem Recht der Mitgliedstaaten erforderlich, dem der Verantwortliche unterliegt.

Die personenbezogenen Daten wurden in Bezug auf angebotene Dienste der Informationsgesellschaft gemäß Artikel 8 Absatz 1 DSGVO erhoben.

Hat der Verantwortliche die personenbezogenen Daten öffentlich gemacht und ist er gemäß Absatz 1 zu deren Löschung verpflichtet, so trifft er unter Berücksichtigung der verfügbaren Technologie und der Implementierungskosten angemessene Maßnahmen, auch technischer Art, um für die Datenverarbeitung Verantwortliche, die die personenbezogenen Daten verarbeiten, darüber zu informieren, dass eine betroffene Person von ihnen die Löschung aller Links zu diesen personenbezogenen Daten oder von Kopien oder Replikationen dieser personenbezogenen Daten verlangt hat.

Das Recht auf Löschung („Recht auf vergessen werden“) besteht nicht, soweit die Verarbeitung erforderlich ist:

zur Ausübung des Rechts auf freie Meinungsäußerung und Information;

zur Erfüllung einer rechtlichen Verpflichtung, die die Verarbeitung nach dem Recht der Union oder der Mitgliedstaaten, dem der Verantwortliche unterliegt, erfordert, oder zur Wahrnehmung einer Aufgabe, die im öffentlichen Interesse liegt oder in Ausübung öffentlicher Gewalt erfolgt, die dem Verantwortlichen übertragen wurde;

aus Gründen des öffentlichen Interesses im Bereich der öffentlichen Gesundheit gemäß Artikel 9 Absatz 2 Buchstaben h und i sowie Artikel 9 Absatz 3 DSGVO;

für im öffentlichen Interesse liegende Archivzwecke, wissenschaftliche oder historische Forschungszwecke oder für statistische Zwecke gemäß Artikel 89 Absatz 1 DSGVO, soweit das in Absatz 1 genannte Recht voraussichtlich die Verwirklichung der Ziele dieser Verarbeitung unmöglich macht oder ernsthaft beeinträchtigt, oder

zur Geltendmachung, Ausübung oder Verteidigung von Rechtsansprüchen.

(6) Recht auf Einschränkung der Verarbeitung

Sie haben das Recht, von uns die Einschränkung der Verarbeitung ihrer personenbezogenen Daten zu verlangen, wenn eine der folgenden Voraussetzungen gegeben ist:

die Richtigkeit der personenbezogenen Daten von der betroffenen Person bestritten wird, und zwar für eine Dauer, die es dem Verantwortlichen ermöglicht, die Richtigkeit der personenbezogenen Daten zu überprüfen,

die Verarbeitung unrechtmäßig ist und die betroffene Person die Löschung der personenbezogenen Daten ablehnt und stattdessen die Einschränkung der Nutzung der personenbezogenen Daten verlangt;

der Verantwortliche die personenbezogenen Daten für die Zwecke der Verarbeitung nicht länger benötigt, die betroffene Person sie jedoch zur Geltendmachung, Ausübung oder Verteidigung von Rechtsansprüchen benötigt, oder

die betroffene Person Widerspruch gegen die Verarbeitung gemäß Artikel 21 Absatz 1 DSGVO eingelegt hat, solange noch nicht feststeht, ob die berechtigten Gründe des Verantwortlichen gegenüber denen der betroffenen Person überwiegen.

Wurde die Verarbeitung gemäß den oben genannten Voraussetzungen eingeschränkt, so werden diese personenbezogenen Daten – von ihrer Speicherung abgesehen – nur mit Einwilligung der betroffenen Person oder zur Geltendmachung, Ausübung oder Verteidigung von Rechtsansprüchen oder zum Schutz der Rechte einer anderen natürlichen oder juristischen Person oder aus Gründen eines wichtigen öffentlichen Interesses der Union oder eines Mitgliedstaats verarbeitet.

Um das Recht auf Einschränkung der Verarbeitung geltend zu machen, kann sich die betroffene Person jederzeit an uns unter den oben angegebenen Kontaktdaten wenden.

(7) Recht auf Datenübertragbarkeit

Sie haben das Recht, die Sie betreffenden personenbezogenen Daten, die Sie uns bereitgestellt haben, in einem strukturierten, gängigen und maschinenlesbaren Format zu erhalten, und Sie haben das Recht, diese Daten einem anderen Verantwortlichen ohne Behinderung durch den Verantwortlichen, dem die personenbezogenen Daten bereitgestellt wurden, zu übermitteln, sofern:

die Verarbeitung auf einer Einwilligung gemäß Artikel 6 Absatz 1 Buchstabe a oder Artikel 9 Absatz 2 Buchstabe a oder auf einem Vertrag gemäß Artikel 6 Absatz 1 Buchstabe b DSGVO beruht und

die Verarbeitung mithilfe automatisierter Verfahren erfolgt.

Bei der Ausübung des Rechts auf Datenübertragbarkeit gemäß Absatz 1 haben Sie das Recht, zu erwirken, dass die personenbezogenen Daten direkt von einem Verantwortlichen zu einem anderen Verantwortlichen übermittelt werden, soweit dies technisch machbar ist. Die Ausübung des Rechts auf Datenübertragbarkeit lässt das Recht auf Löschung („Recht auf Vergessen werden“) unberührt. Dieses Recht gilt nicht für eine Verarbeitung, die für die Wahrnehmung einer Aufgabe erforderlich ist, die im öffentlichen Interesse liegt oder in Ausübung öffentlicher Gewalt erfolgt, die dem Verantwortlichen übertragen wurde.

(8) Widerspruchsrecht

Sie haben das Recht, aus Gründen, die sich aus Ihrer besonderen Situation ergeben, jederzeit gegen die Verarbeitung Sie betreffender personenbezogener Daten, die aufgrund von Artikel 6 Absatz 1 Buchstaben e oder f DSGVO erfolgt, Widerspruch einzulegen; dies gilt auch für ein auf diese Bestimmungen gestütztes Profiling. Der Verantwortliche verarbeitet die personenbezogenen Daten nicht mehr, es sei denn, er kann zwingende schutzwürdige Gründe für die Verarbeitung nachweisen, die die Interessen, Rechte und Freiheiten der betroffenen Person überwiegen, oder die Verarbeitung dient der Geltendmachung, Ausübung oder Verteidigung von Rechtsansprüchen.

Werden personenbezogene Daten verarbeitet, um Direktwerbung zu betreiben, so haben SIe das Recht, jederzeit Widerspruch gegen die Verarbeitung Sie betreffender personenbezogener Daten zum Zwecke derartiger Werbung einzulegen; dies gilt auch für das Profiling, soweit es mit solcher Direktwerbung in Verbindung steht. Widersprechen Sie der Verarbeitung für Zwecke der Direktwerbung, so werden die personenbezogenen Daten nicht mehr für diese Zwecke verarbeitet.

Im Zusammenhang mit der Nutzung von Diensten der Informationsgesellschaft könne Sie ungeachtet der Richtlinie 2002/58/EG Ihr Widerspruchsrecht mittels automatisierter Verfahren ausüben, bei denen technische Spezifikationen verwendet werden.

Sie haben das Recht, aus Gründen, die sich aus Ihrer besonderen Situation ergeben, gegen die Sie betreffende Verarbeitung Sie betreffender personenbezogener Daten, die zu wissenschaftlichen oder historischen Forschungszwecken oder zu statistischen Zwecken gemäß Artikel 89 Absatz 1 erfolgt, Widerspruch einzulegen, es sei denn, die Verarbeitung ist zur Erfüllung einer im öffentlichen Interesse liegenden Aufgabe erforderlich.

Das Widerspruchsrecht können Sie jederzeit ausüben, indem Sie sich an den jeweiligen Verantwortlichen wenden.

(9) Automatisierte Entscheidungen im Einzelfall einschließlich Profiling

Sie haben das Recht, nicht einer ausschließlich auf einer automatisierten Verarbeitung – einschließlich Profiling – beruhenden Entscheidung unterworfen zu werden, die Ihnen gegenüber rechtliche Wirkung entfaltet oder Sie in ähnlicher Weise erheblich beeinträchtigt. Dies gilt nicht, wenn die Entscheidung:

für den Abschluss oder die Erfüllung eines Vertrags zwischen der betroffenen Person und dem Verantwortlichen erforderlich ist,

aufgrund von Rechtsvorschriften der Union oder der Mitgliedstaaten, denen der Verantwortliche unterliegt, zulässig ist und diese Rechtsvorschriften angemessene Maßnahmen zur Wahrung der Rechte und Freiheiten sowie der berechtigten Interessen der betroffenen Person enthalten oder

mit ausdrücklicher Einwilligung der betroffenen Person erfolgt.

Der Verantwortliche trifft angemessene Maßnahmen, um die Rechte und Freiheiten sowie die berechtigten Interessen der betroffenen Person zu wahren, wozu mindestens das Recht auf Erwirkung des Eingreifens einer Person seitens des Verantwortlichen, auf Darlegung des eigenen Standpunkts und auf Anfechtung der Entscheidung gehört.

Dieses Recht kann die betroffene Person jederzeit ausüben, indem sie sich an den jeweiligen Verantwortlichen wendet.

(10) Recht auf Beschwerde bei einer Aufsichtsbehörde

Sie haben zudem, unbeschadet eines anderweitigen verwaltungsrechtlichen oder gerichtlichen Rechtsbehelfs, das Recht auf Beschwerde bei einer Aufsichtsbehörde, insbesondere in dem Mitgliedstaat ihres Aufenthaltsorts, ihres Arbeitsplatzes oder des Orts des mutmaßlichen Verstoßes, wenn die betroffene Person der Ansicht ist, dass die Verarbeitung der sie betreffenden personenbezogenen Daten gegen diese Verordnung verstößt.

(11) Recht auf wirksamen gerichtlichen Rechtsbehelf

Sie haben unbeschadet eines verfügbaren verwaltungsrechtlichen oder außergerichtlichen Rechtsbehelfs einschließlich des Rechts auf Beschwerde bei einer Aufsichtsbehörde gemäß Artikel 77 DSGVO das Recht auf einen wirksamen gerichtlichen Rechtsbehelf, wenn sie der Ansicht ist, dass Ihre, aufgrund dieser Verordnung zustehenden Rechte, infolge einer nicht im Einklang mit dieser Verordnung stehenden Verarbeitung Ihrer personenbezogenen Daten verletzt wurden.

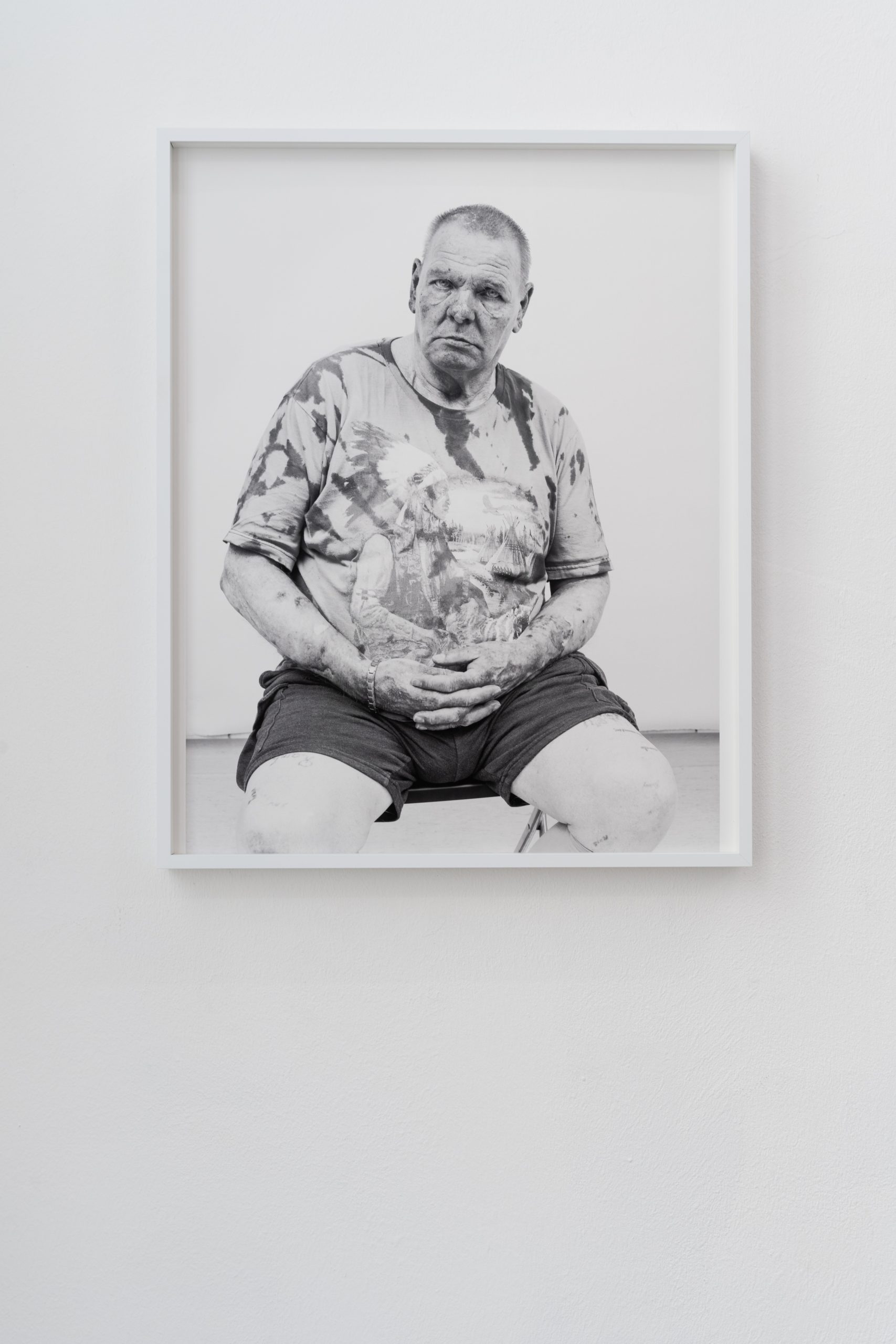

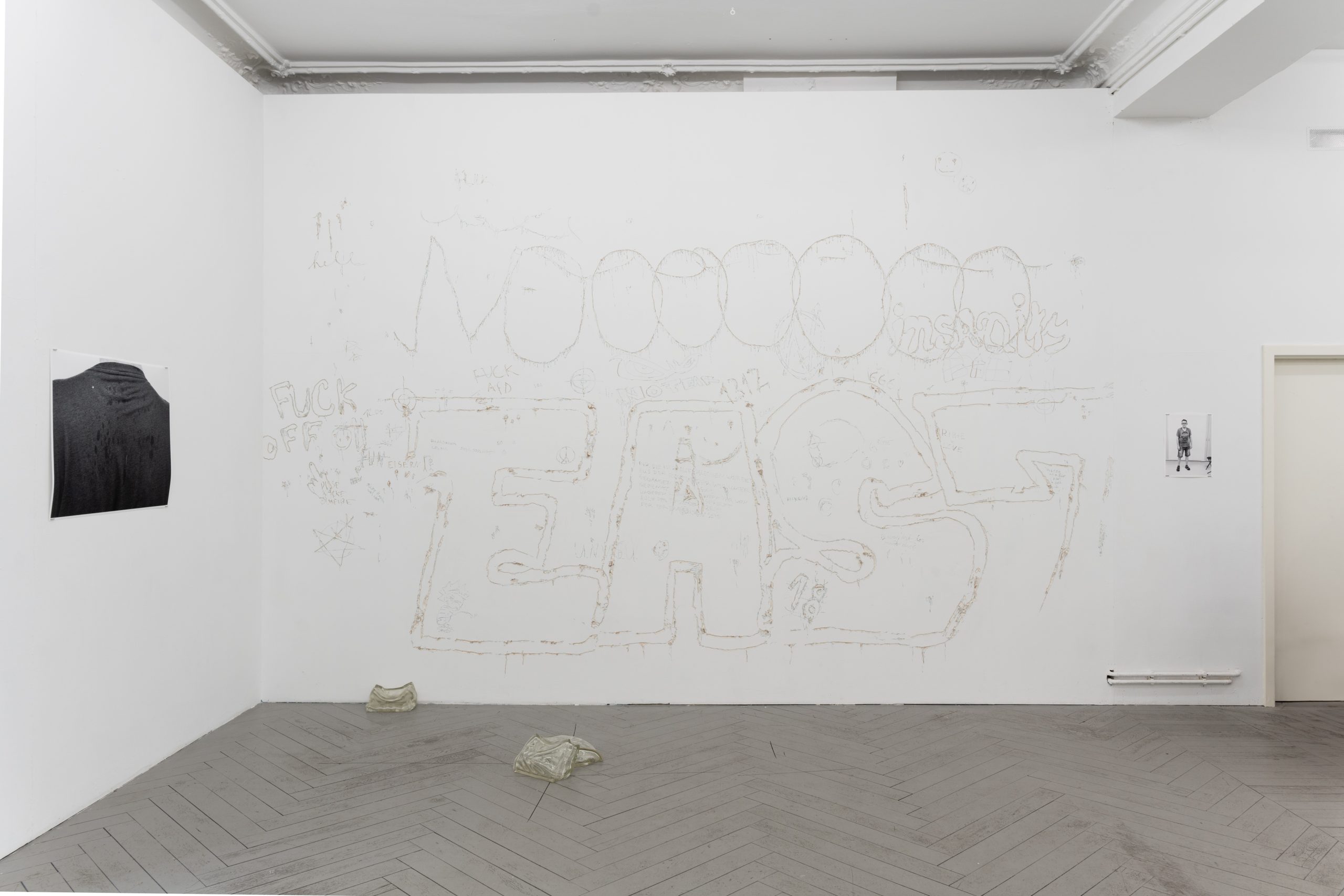

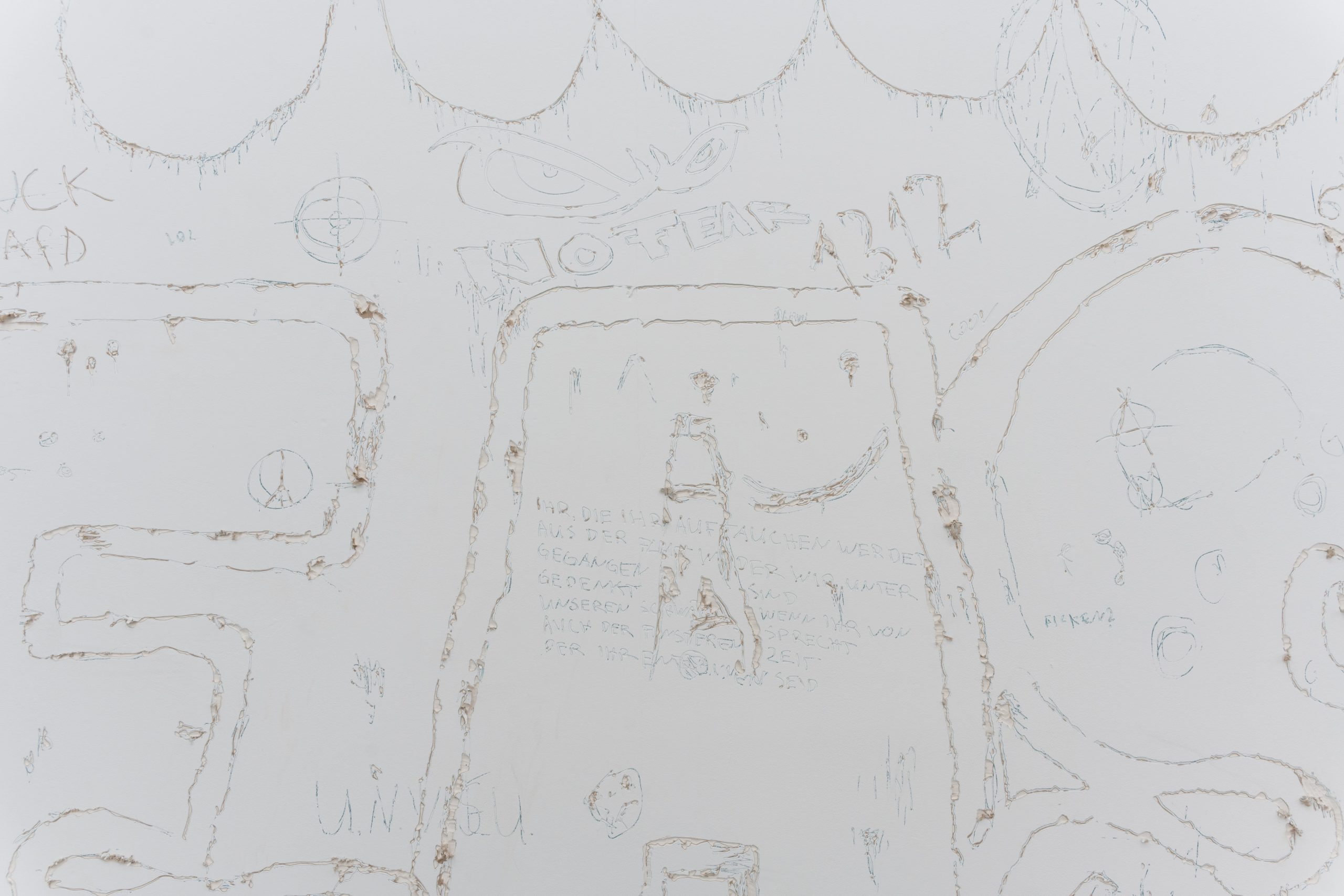

Photo: Dani d’Ingeo, courtesy the artist and Club Are.

Photo: Dani d’Ingeo, courtesy the artist and Club Are.

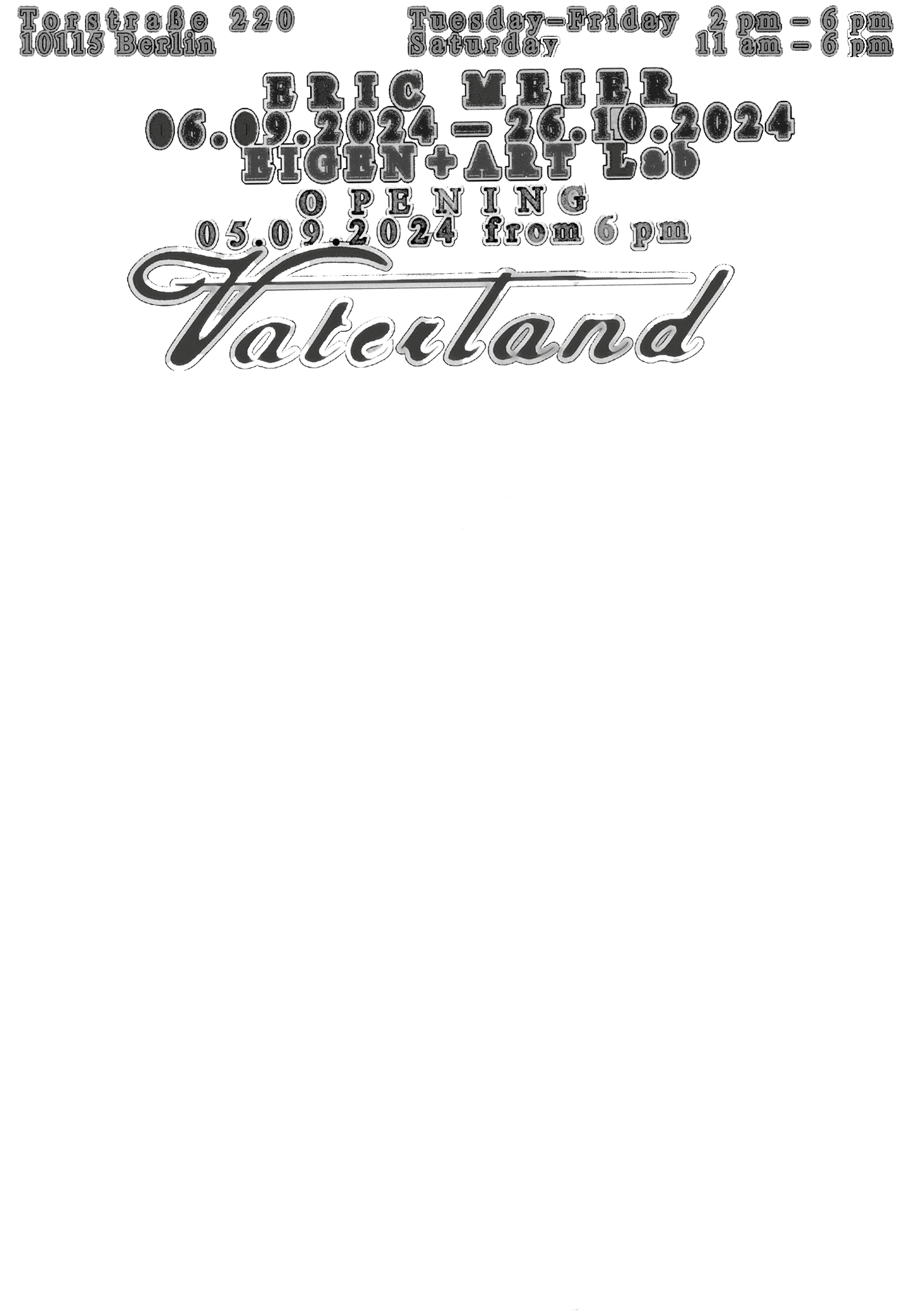

Design by NEXT HOUSE OVER

Design by NEXT HOUSE OVER Design by NEXT HOUSE OVER

Design by NEXT HOUSE OVER